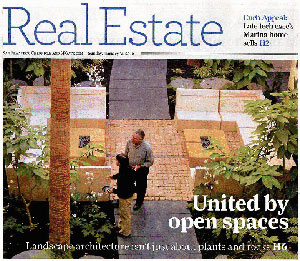

Bringing the indoors outdoors

San Francisco landscape architect is trying to use his designs to unite residents

The San Francisco Chronicle

by By Jeremy Schnitker, Sf.BlockShopper.com

January 31, 2010

For Jeffrey Miller, landscape architecture is more than just plants, waterfalls and decorative rocks. For Miller, the founder of San Francisco’s Miller Company Landscape Architects, it’s about uniting living spaces and bringing people together.

“My impetus to be a landscape architect came out of a question – how to design social and public space so that there were better relationships between people,” he said. “It wasn’t a nature-based beginning, it came from more of a sociological perspective.”

Since forming Miller Company in 1980, the former sociology student and filmmaker has been involved with some of the more dramatically landscaped residential communities in the Bay Area. He’s worked on developments such as Pacific Cannery Lofts and Zephyr Gate in Oakland, the Emeryville Lofts in Emeryville, and Potrero Heights at 18th and Arkansas streets in San Francisco. Anybody who has been to any of those projects will notice a common theme: They’re designed to increase interaction among their residents.

Take Pacific Cannery Lofts, for example. The development, which is built around an old cannery warehouse, has a dining room entry court and a living room courtyard with two large U-shaped seating arrangements. A linear garden grove runs between the condo units in the cannery building and the three-story townhouses that were built just to its east.

“That grove is sort of a garden street extension of Pine Street into the project,” said Kevin Wilcock, a partner with David Baker + Partners architects, which designed Pacific Cannery Lofts. “The units are accessed off of that grove, and people hang out on the raised porches there, and its setup really encourages interaction and circulation throughout the complex.”

Miller says that making a more sociable living space is pretty simple. One tactic: Create seating areas where people can sit directly across from each other.

“The outdoor seating is set up so that people can look at each other when they sit,” he said. “Oftentimes you see public benches that are built in a linear fashion that doesn’t allow people to face each other.”

These days, Miller says, he is keenly interested in the “edges” of developments, devising ways to connect subcommunities within the Central Station neighborhood in Oakland. To that end, he’s worked to weave the Pacific Cannery Lofts and Zephyr Gate together, and he hopes to tie them to a third planned apartment complex nearby.

“We’ve built walkways that go from one development to the other, and we worked to adjust certain building layouts so that a pedestrian could go from one place to another without going around everything,” he said.

Another common theme of Miller’s work is taking on projects in neglected urban areas – overrun with steel and concrete – and subtly infusing them with greenery and water flow.

“At the core of all of this is a notion that we’re being subliminally affected by the landscape, and it’s not screaming out at you right at your face that this is all obvious and logical,” he said.

And the Bay Area is perhaps as appropriate a playground for innovative landscape architecture as any in the country. With its temperate climate and ample sunshine, it’s an ideal locale.

“I think landscape architecture is just as important as good architecture as far as I’m concerned, especially here in California,” said Rick Holliday, founder and president of Holliday Development, which has worked on a handful of projects with Miller over the last two decades. “You know, if we were in Manhattan, it probably wouldn’t matter; you’d just have put some plants in hallways. But here, you really want the outside to come inside and the inside to come outside. People want to have a relationship with the outside in Northern California, and doing that well is critical to doing good infill housing.”

Miller, who grew up in Southern California and was educated on the East Coast, but has called Northern California home for roughly the last 35 years, says the terrain here gives landscape architects unique challenges.

“We basically live in a desert in California, and all of our water is imported from one place or another, so there’s a tremendous need for landscape architecture to help turn this desert that we live in into a livable environment,” he said.

Ultimately, Miller realizes that the outdoor space of a development is almost always larger than the interior space, and what you do with that is as important as creating comfortable living rooms and spacious kitchens.

“The largest space that we have with these projects is everything that’s outside of the buildings,” he said. “So the care and design of the world outside of buildings is tremendously important to the way we live, especially in urban places. This is kind of our public living room – what we have outside – and the more we can create sociable environments for communities coming together, the better social environment we’re going to have.”