It’s Oakland’s turn

The lowdown on restaurants, politics, art, real estate, and more in the Bay Area’s next great scene.

SAN FRANCISCO MAGAZINE

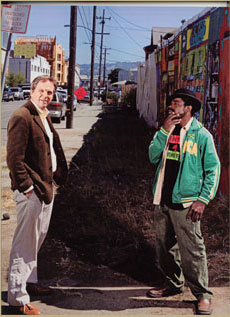

by Edited by Nan Weiner Photos by Jamie Kripke

October 1, 2007

After I failed to find easy parking in Old Oakland for the second weekend in a row, the unfamiliar thought flashed through my mind: “All these damn bridge-and-tunnel types are starting to ruin this town.” I was only half joking. It was a Saturday evening, and B Restaurant was already rocking. No spaces on Washington Street. A new design gallery, Fiveten Studio, brainchild of the prolific Alfonso Dominguez (he co-owns the intimate Old Oakland restaurant Tamarindo), was having an opening around the corner. Some of the most beautiful people I’d ever seen in my adopted hometown were smiling brightly and sipping champagne outside the well-lit space. The entire block was closed off, anyway, so the city could show a free movie after sunset. No parking on Ninth, either.

At one point, I found myself cruising all the way down near Jack London Square. On Second Street, a dark-clad crowd of impossibly thin kids in their late teens and early 20s waited, like roosting crows with a bad tobacco habit, to get into the Oakland Metro Operahouse. I could hear the throbbing bass of a punk band checking its sound. I circled back, parked five blocks from my destination, and made my way to plush Levende East (sister of Levende Lounge in San Francisco), where the dinner crowd was an unself-conscious mixture of old and young, black and white, Asian and Latino—that’s Oakland—but the air had an intriguing snootiness, or a whiff of it, that I hadn’t encountered anywhere this far outside Rockridge. I love this city of 400,000 people, its very American history, its polyglot populace, its industrial blocks and beautiful buildings and wild spaces, its aura of countercultural romance. But I’ve often felt it lacked any real urban buzz and a certain cosmopolitan instinct for self-promotion. So I took all this as a good sign.

These days, even important streets can still seem deserted when they ought to be humming—the lights go out early in semiurban Oakland—but more and more, the necessary elements of a metropolis are finding their way east. Street by street, the city is coming into its urban own—one nightclub, art gallery, renovated building, shop, restaurant, and condo at a time. As would-be San Francisco homeowners and businesses chafe at the cost of living and operating there, Oakland finds itself on a relentless drive toward a modern-day revitalization akin to what happened south of Market in the ’90s, or the incursion of youthful hipness Brooklyn has seen in the past decade.

Signs of new energy are everywhere. With a half-dozen enormous condo projects nearing completion, Oakland’s downtown is on the verge of hosting the kind of diverse, 24-7 life that animates every block and causes entrepreneurs to begin sniffing out opportunities. Restaurants and bars—some elegant, some noisy and rife with sexual energy, some quiet and friendly—are already sprouting, like long-dormant bulbs that have finally gotten water. Art galleries are reinvigorating neglected spaces all over the city. Whole Foods is opening its first store in Oakland (Trader Joe’s is readying two), and next to Lake Merritt, the most expensive cathedral in U.S. history unveils more of its compelling shape each day.

There are promising signs that no part of the city is being bypassed. Redevelopment projects are adding new life to the upper reaches of International Boulevard, while facade-improvement programs are raising profiles and pride in Fruitvale. Even in West Oakland, the once grand, now dilapidated 16th Street Train Station is slated for a commercial metamorphosis over the next three years, alongside three new housing developments—the first major private investment in the area in four decades. And while it’s only a drawing now, the East Oakland no-man’s-land around the Coliseum has been targeted for a redesign meant to brighten a blighted stretch of the city without denying its industrial character.

“Given its complexities and its problems,” says Phil Tagami, a developer with deep roots here, who’s currently revamping the Fox Theater, on Telegraph, “what Oakland is doing is amazing.”

How has this happened? Partly, it’s a matter of urban homesteaders unable to resist Oakland’s beauty and soul—and its affordability—in spite of its well-known crime problems. Increasingly, you can spot their handsomely restored Victorian and Italianate houses dotting the streets of West Oakland. Some credit forward-thinking companies like Essex, Signature, and Bridge Housing, which have been willing to take a risk—to bring luxury to Lake Merritt, for example, and commerce to long-neglected neighborhoods. Some say it all began with former mayor Jerry Brown’s business-friendly Big Idea: 10,000 new souls living in the heart of the city. Still others credit the economy, stupid—Oakland, they say, is simply soaking up the benefits of the recent tech and real estate booms. “The national market was so incredibly hot,” says Gregory Hunter, the head of redevelopment for the city, “that Oakland was due to get its share.” Indeed, developers saw the high prices people were paying for houses and suddenly realized there was money here, too.

Together, Oakland’s pioneers are slowly creating a pulse-lifting scene in the gritty, historic blocks that lie between the blandness of Jack London Square and the commercial ennui of Broadway Auto Row. If those two unfortunate projects represent Oakland’s misguided recent past, Uptown—with its Forest City housing development and the impending return to glory of the Fox Theater—may well represent the city’s brighter future.

Thomas Schnetz has a pretty good feel for these things. He led the way in Temescal, upper Telegraph Avenue’s tree-lined culinary haven, by opening Doña Tomas eight years ago, and his new restaurant, Flora, is about to open in the renovated art deco Floral Depot Building in Uptown. “The Fox will become a landmark again, and all these restaurant people are moving down there,” he says. “The neighborhood is just ready to pop.”

Developer Andrew Brog is banking on it. He’s bought three beautiful buildings in Uptown and Old Oakland, the other rapidly evolving neighborhood downtown. After failing in bids to acquire buildings in San Francisco, Brog made his first trip to Oakland in 2005, got off at the 12th Street BART station, and took the escalator up.

“I felt like I was back in New York City,” says the East Coast native. Parts of downtown reminded Brog of areas of Lower Manhattan—Chelsea and the East Twenties—where he’d done transformation projects, neighborhoods that are now some of the trendiest in the trendiest city in the world. “There’s not one bad neighborhood in Manhattan anymore,” he says, “and the same thing can happen in Oakland.” So in the Golden Bridge Lofts and the Marquee Lofts—each of which looks like it could have been airlifted here from SoHo—and inside the Gothic splendor of the flatiron Cathedral Building, Brog is laying the seeds of an upscale enclave like Oakland hasn’t seen since these architectural gems were built, back in the early 20th century, when Oakland was roaring. Uptown, currently populated by dive bars and funky art galleries, may well transform into the kind of bright lights, big city strip that old-timers will lament 10 years from now, remembering the days in 2007 when it was still slightly dirty and too dimly lit. And still cool.

And it is just such a potential shift that makes me question my own breathless paean to Oakland’s new excitement. It makes me wonder where the city is headed, and who exactly will be raised up by all this flux.

So far, Oakland’s makeover seems to be resisting the you-could-be-anywhere development that plagues many reborn cities across America. “We didn’t believe the people of Oakland wanted that,” says the owner of the Uptown Nightclub & Bar, Kevin Burns. “We don’t need a high-end Denny’s.” Instead, what’s happening here feels less like the mallification of mid-Market Street or (God forbid) downtown Walnut Creek and more like a discovery, as cool and new mix with cool and old in neighborhoods like Old Oakland and Temescal. In both these neighborhoods, new shops like Drift and restaurants like Pizzaiolo have reinvigorated old storefronts and old blocks, while attracting crowds that reflect Oakland’s vibrant eclecticism.

But what happens when word gets out? Will I look up one day and see a Hard Rock Cafe or some other neon harbinger of generic doom? Will there come a moment five years from now when I hunger for the former unpretentiousness of Oakland and can’t find it?

Other, more urgent worries persist as well. The city’s historic inability to attract major retailers to downtown could strangle the life from its independents. Certainly the whims of the real estate market could halt Oakland’s progress, as could a seemingly detached mayoral administration.

So could the city’s recurring violence. The brazen murder of journalist Chauncey Bailey brought national attention, but as we all know, here at home the papers are filled with such stories all the time. Sometimes late at night, from my house on a little hill in Glenview, I can hear the pop pop pop of death in the lowlands to the east, where old and young are being gunned down with a frequency no great city can bear. Despite the promise of new development, the powerless citizens of East and West Oakland could easily be left on the edge of this boom, waiting and hoping for something to trickle down from whatever prosperity it creates. Ten years from now, will the headlines still scream “Death in Oakland” while I squeeze through a crowd of white, well-dressed theatergoers exiting the gleaming, reborn Fox Theater?

Of course, change is nothing new in cities. When I ask Betty Marvin, the Oakland Planning Commission’s history maven, if Oakland is on the verge of something big, she tells me they said the same thing in the newspapers as far back as the 1880s. To Marvin, today’s boosters—some of them, anyway—are just another era’s Johnny-come-latelies bent on making a place that is already great conform to their own trendy, but possibly fleeting, vision of what a city should be.

I wholeheartedly agree with Marvin’s basic message that Oakland is a wonderful place. But I embrace many of the changes I see. I like the new liveliness that straddles Broadway and Telegraph, even if parking is becoming a pain. I like the cranes that swing in the air. I like that there are people and businesses willing to embrace the uncertainty of it all. And I like that, so far, what’s always been great about Oakland—its industry, its diversity, its coolness, its trees—has not been pushed aside by what’s new about Oakland. It’s as if the providers of urban amenities, and all the new arrivals pursuing them, have had the same simple epiphany that goes something like this: Ah, Oakland. Beautiful, soulful, raw. And stirring.

James O’Brien is a writer living in Oakland’s Glenview district and a correspondent for GQ.